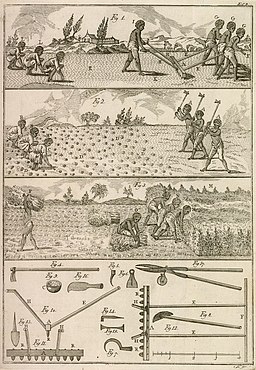

We think of Jamaica as the great home of sugar production in the eighteenth century, which of course it was, but in the early days of colonisation and well into the eighteenth century indigo was also an important crop. Although the image above is from Brazil, the method of cultivation and the use of slave labour was much the same in Jamaica.

Originating in India the indigofera tinctoria plant came to replace the use of woad for blue dye in medieval Europe, and the colour is perhaps most familiar to us now for its use in dying denim jeans, although synthetic dyes now widely replace natural indigo.

To make the dye the plant is usually cut and placed into large fermentation vats for about 15 hours after which the yellow liquid can be used immediately for dying cloth, which turns blue as it is removed on contact with the air. Alternatively the liquid is strained off through a series of large vats and agitated to oxygenate it until it changes colour and finally precipitates out as flakes. The pulp is strained, boiled with fresh water to remove impurities and filtered through coarse linen or woollen bags, until finally it can be cut into cakes and air dried ready for transport or sale.

Modern Indigo block from India

Photo by Evan Izer (Palladian) (Own work) [CC-BY-SA-2.5 (www.creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.5)], via Wikimedia Commons

There was huge demand for blue dye in the eighteenth century and although the East India Company developed cultivation in Bengal that would eventually displace other areas, indigo was cultivated in Jamaica from the second half of the seventeenth century as a possible alternative to tobacco and one needing a smaller labour force than sugar, labour that was mostly required for cutting and processing the plants.

When Thomas Modyford surveyed Jamaica in 1670 he recorded “49 Indigo works which may produce about 49,000 weight of Indigo per annum, to which many more works are daily adding”.

The Newcastle Courant for Wednesday 15 October 1712 reported that “Yesterday arrived the Providence Galley from Jamaica, but last from Shields, laden with Sugar, Cacao, Indigo etc.”

Twenty years later the Derby Mercury of Thursday, 24 August 1732 reported a serious shortage of indigo with the arrival of a ship at Bristol ten days earlier. “The last Ship arrived here from Jamaica has brought but one small Barrel of Indigo, that Commodity being very scarce there, so that we shall receive but very little, if any, this Year which is likely to make a great Alteration in the Price, Indigo being already in very great Demand here.”

At just about this time when there was a scarcity of Indigo from Jamaica, South Carolina was developing an industry to displace Jamaica as a main exporter, while Jamaica increasingly found greater profit to be made by the export of sugar. Nevertheless, it was still possible to make a good living as an Indigo planter which remained a minor export crop along with cocoa, ginger and pimento.

Dyeing blue linen

Take half a pound of indigo, and grind it well with a little lime water into an impalpable paste. Put it into 10 gallons of cold water, and add half a pound of Potash. 1 lb green copperas, 3 lbs quicklime. Let the whole stand till there forms on the surface a copper coloured head, and the liquor underneath appears yellow-green. Dip the linen in this liquor till it has acquired the shade of colour desired.

Josiah Wedgwood’s Commonplace Book n.d., page 44 Wedgwood MS 39-28408. (http://www.gutenberg-e.org/lowengard/C_Chap35.html)

Linen was widely used for shirts and underwear and perhaps surprisingly it was sometimes dyed blue, whether for fashion or because it showed the dirt less is unclear. There is a set of blue dyed linen panniers – hoops for supporting a skirt – illustrated in the fascinating “The History of Underclothes” by C Willett and Phillis Cunnington (Dover, 1992), and a wonderful seventeenth century description of young women running a race in their differently coloured drawers.

For the more up-market uses of indigo you have only to look at the wonderful portraits by Joseph Wright of Derby in which so many of the prosperous provincial ladies wore blue satin.

And while I’m on the subject of Joseph Wright, The Derby Museums and Art Gallery are opening a newly refurbished gallery displaying Wright’s works on February 25th 2012. Do visit if you can.