Coal boats loading at North Shields c.1795 – J M W Turner (via Wikimedia Commons)

It’s that time of year when preserving garden produce for the winter is on my mind. It’s been a fantastic year for fruit in the UK and there is a glut of apples and pears, we’ve had a huge crop of blackberries and the wild rowan trees are covered in berries.

Checking the cupboard for sugar to make crab apple and blackberry jelly I found some left from last year that had hardened in the packet and that made me think of the labour involved in preparing sugar for use in the eighteenth century. Once the cane was cut and the juice boiled and crystalised most was packed into barrels for transport to Europe and further processing there. Only a small amount was ‘clayed’, further refined into white sugar loaves, in Jamaica. This was to protect the interests of the sugar bakers in Britain.

Either way the sugar bought by the eighteenth century housewife came in hard loaves from which the sugar had to be rasped or broken off and then pounded to the consistency required. Imagine taking a bag of modern sugar crystals and pounding it down to produce your own icing sugar and you will get an idea of the sheer physical labour involved and the time it took.

Then remember that to cook using your sugar you would have to light and tend your kitchen fire. By the eighteenth century London was dependent on imported coal as the medieval forests that once covered the country had been cut down for domestic fuel and for early industry. You would have ordered your coal using the old measure of a ‘chaldron of coals’, an amount which could vary from about 2000 pounds weight upwards. A London chaldron was defined as “36 bushels heaped up, each bushel to contain a Winchester bushel and one quart, and to be 191⁄2 inches in diameter” (source:Wikipedia). The weight of this was about 3136 pounds so it was no wonder that a limit was put on the amount that could be drawn in one wagon – incidentally to protect the road from excessive wear rather than the horses from exhaustion!

When the coal was delivered to your house you would have to inspect it to make sure the merchant was not cheating you by including poor quality coal, wet coal or a load full of small dust called ‘slack’. It would be shovelled by hand from the wagon into your cellar or shed and from there you or your servants would have to scoop it up into the coal scuttles for use in kitchen and living rooms. Little wonder that only the well to do had fires in their bedrooms in even the coldest of weather.

Everything that happened in the eighteenth century household involved physical labour on the part of the householder or the servants. Preparing meals meant walking to market for the ingredients, scrubbing and preparing the vegetables, plucking the poultry, rendering your own fat from pork or beef to produce dripping, beating the eggs and ingredients for cakes (my grandmother beat fat and sugar for an eggless sponge by hand – that is using her own hand not a beater, the beating took up to half an hour but she made a superbly light sponge!). Even so simple an act as writing a letter might still involve mixing your own ink, and would require you to cut your own quills – paper you could at least buy ready made.

Leaving aside the digital revolution, think of any task you now undertake and then take yourself back to a time when there was no electricity, and virtually no machinery to assist. You could buy the cloth and thread for your clothes, but you or someone else would have to make the pattern, cut the cloth and sew them by hand. When they got dirty they would have to be washed by hand using soap you made yourself, although in London the air was now so filled with soot that those who could afford it sent their linen out of town to washer women in the outlying villages. If the weather was cold the water might freeze in the pump and in any case it would all have to be carried by hand to where it was needed.

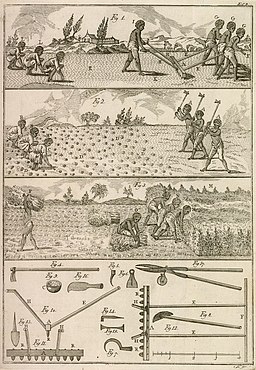

In eighteenth century Jamaica the source of cheap labour that made all this possible was of course enslaved, while London and the growing cities such as Manchester and Birmingham were sucking in labour from the surrounding countryside. The nineteenth century would see a huge change with a move from human to machine power and a gradual increase in the cost of labour, with a corresponding decrease in the relative cost of machine power. We are much closer to this nineteenth century world than we are to that of the eighteenth.

So next time you put sugar in your coffee, boil a kettle, load the washing machine, cut the lawn or drive to the supermarket to load up with ready prepared goods, just pause for a moment and imagine having to do all these tasks the eighteenth century way.