London Bridge – late 18th century – the waterwheels can be seen at far end of the bridge

I have written before about John Serocold and his son of the same name who were Jamaica merchants during the 18th century, based in London. John Serocold senior was married to Martha Rose one of the daughters of Captain John Rose who made some of his money transporting rebels to Jamaica after the Monmouth Rebellion[1].

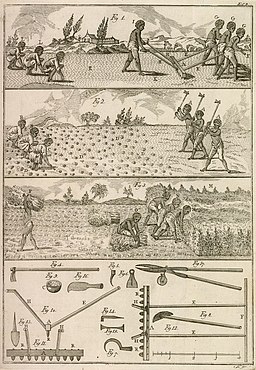

9 December 1685 – Invoice of sixty eight men servants, shipped on board, Capt Charles Gardner, in ye Jamaica Merchant (ship) for account of Mr.Rose and Comp.,they being to be sold for ten years..

Martha’s sister Elizabeth married Samuel Heming and had at least five children baptised in Jamaica. Another sister Frances married Dr John Charnock and had two children baptised and died in Jamaica before his death at St John’s in Jamaica in 1730. Afterwards she returned to London and married wealthy merchant Robert Fotherby who had a position in the Royal African Company and was almost certainly dealing in slaves shipped to the West Indies.

Mary Rose, older than her sisters, married first Thomas Halse of Halse Hall, then John Sadler and finally wealthy merchant John Styleman after her return to London. You can read more about her here.

Martha Serocold died after presenting John Serocold with the second of two daughters both of whom died in infancy, and three years later he remarried with his second wife producing two sons – John and Thomas. John carried on his father’s business trading with Jamaica, later as the firm of Serocold and Jackson, in partnership with his son-in-law John Jackson.

The company of Serocold and Jackson got into severe financial difficulties but came to an arrangement with its creditors in 1782 (Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette – Thursday 28 March 1782). Given the date it is not impossible that their troubles were connected with the disasters of the hurricane years in the early 1780s. They must have continued to struggle, for in 1786 John Serocold of Love Lane in the City of London was declared bankrupt. At his death two years later John Serocold was described as ‘formerly an eminent West India Merchant’ (Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette – Thursday 13 November 1788). His brother Thomas outlived him by several years, having opted for the life of country gentleman at Peterborough.

I was intrigued by the name Serocold which is quite unusual, and all the more so when I came across George Sorocold who is often credited with being Britain’s first great civil engineer and who was the designer of the world’s first factory, Derby’s Silk Mill.

George Sorocold was a quite remarkable man, but the dates of his birth and death are unknown. He was probably born about 1666 and died after 1738. It seems likely that his family origins were in Lancashire but this is difficult to establish with any certainty partly because there are so many different versions of the name. So far I have found the following variant spellings, some in original documents and some in transcriptions: Sorocold, Sorrocolde, Sorrocoulde, Soracowle, Sorocale, Sorracoll, Seracold, Serocold, Sarracold.

I have as yet found no evidence for the suggestion made by others that his father was James Sorocold who had already moved to Derby when George Sorocold married there in 1684.

There is no record of how George acquired his education and when I first saw that he appeared to have married at the age of sixteen I was inclined to disbelieve it since this would be unusually early for an educated man of middle or upper-class origins. However I then found a more or less contemporary account which suggested that his wife had already had thirteen children (with no multiple births) eight of whom were still living by the time George was twenty-eight – pretty much a mathematical impossibility unless he had fathered his first child aged fifteen or sixteen. Perhaps it was a shotgun wedding!

The account of Sorocold’s fecundity was recorded in 1715 by a man called Thoresby who knew Sorocold, and who had an interest in compiling accounts of very large families, including Jane Hodson who according to her epitaph in York Minster, died on September 2, 1636, aged 38, during the birth of her 24th child and another woman said to have had 53 children in 35 births.

They made them tough in those days!

It is a shame that we don’t know more about George Sorocold since his achievements in civil engineering were very considerable. He created a public water supply for Derby by raising water from the river Derwent into a tank that supplied a pipe system that lasted into the nineteenth century. Moreover the waterwheel was designed to rise and fall with the water level in the river to maximise supply even in periods of dry weather.

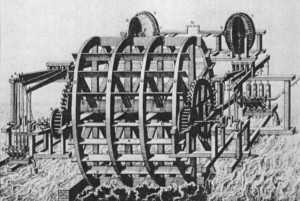

He went on to work on a system of waterwheels and pumps under Old London Bridge and created the public water supply in a number of major cities including Leeds. At Liverpool he engineered the city’s first wet dock, contributing indirectly to its rise as a major slaving port.

Waterwheels at Old London Bridge about 1700

Interest in George Sorocold’s engineering achievements means that there is now research on-going to try to find out more about his origins and background. It seems highly likely that there is a connection between the Sorocolds of Lancashire, the merchant Sorocolds of London and the eminent engineer George Sorocold – a work in progress.

Pictures are taken from Old London Bridge where you can find the history of the changes that took place during the eighteenth century when the old bridge was modernised before being completely replaced in the nineteenth century.