The Court of Chancery in the reign of George I (source: Wikipedia)

The Court of Chancery in the reign of George I (source: Wikipedia)

The case of Francis March against members of the Ellis family is very typical of 18th-century Jamaican Chancery cases. Many of these arose because of the early deaths of colonists and their reliance on loans taken out in expectation of repayment from the profits of their estates, profits which did not always materialise. Add to this the problems of remote management of estates for absentee owners, inadequate record keeping, records lost by accident or destruction by the Jamaican climate, and you have a difficult mix in which disputes about Wills and land ownership could drag on for many years.

Moreover decisions of the Jamaican court had to be ratified in England and so a litigant might find themselves fighting in the courts of both Jamaica and London. This is the context of a case that spanned the first quarter of the eighteenth century involving the descendants of John Ellis and his son-in-law Francis March.

John Ellis arrived in Jamaica either with or shortly after the first group of colonists and rapidly acquired several estates and plantations. When he died in August 1706 he left three of 11 children still living – John, George and Martha. His daughter Martha had married Frances March in 1701 when she was 17 and he was about 21 and Ellis appointed his son-in-law as one of his Executors.

John Ellis junior married Elizabeth Grace Nedham (sometimes written Needham) and they had four children living at his early death in England only three years after his father. John the elder had left legacies to his daughter Anne, and to his grandchildren Sarah and John March as well as to the poor of the parish of St Katherine’s. The bulk of his estate was left to his son John, who on his death had made a will leaving £2000 Jamaican currency to each of his daughters Mary and Martha when they married, plus an additional £1000 to each of their first children. He left £1000 to his sister which appears to have been due to her from their father’ s will and £500 to Abigail Demetrius who was then a minor. Having made provision for the education of all his children and Abigail he left various parcels of land to his son George making his elder son John residuary legatee. This third John Ellis later died without having made a will or having married.

As Executor Frances March apparently discovered after the death of the second John Ellis that none of the legacies due from John Ellis the elder had been paid and that John Ellis the younger had died in debt to the tune of over £8000 (which would have a purchasing power of nearly £900,000 today).

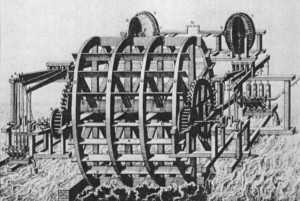

The Ellis property in Jamaica consisted of the Caymanus Plantation, a large part of the Crawle Plantation, two thirds of the Sixteen Mile Walk Plantation, plus some other uncultivated land and all the associated sugar works, slaves, stock and equipment.

The Sixteen Mile Walk Plantation was owned in part by Susanna Cooke who had leased it to a man called Carlton Goddard in return for an income of £50 per year, and in about 1704 the younger John Ellis had agreed to buy out Carlton Goddard’s share for £1800, paid in instalments with interest. Ellis took possession of the land, but failed to pay most of the money and all of the rent.

Before the legal formalities had been completed conveying the land to John Ellis, Carlton Goddard was declared bankrupt and his Jamaican property was assigned to a London merchant called Samuel Clarke. Francis March, who was then in Jamaica, was sending money back to London for the maintenance of the four Ellis children and their aunt Anne Ellis, and he was now faced with the demand from Samuel Clarke to hand over Goddard’s share of the Sixteen Mile Walk Plantation. March told Clarke that the conveyance had not been completed but Clarke agreed to the conveyance going ahead on payment of the Ellis debt by March in person out of his own funds.

Meanwhile by about 1712 Susanna Cooke had died, and a man called John Hayward offered to buy out her son George Cooke’s share of Sixteen Mile Walk and his share of the Crawle Plantation and various other pieces of land, which had he succeeded would have seriously affected the value of the Ellis properties. So Francis March set out for England to get agreement from George Cooke in person to sell all this property to him. Again March paid for this from his own funds intending it for the benefit of his own family and about Christmas 1713 he travelled back to Jamaica and attempted to sell John Ellis’s “wastelands”, as requested under the terms of the will. He sold a small amount of land to Ezekial Gomersall, but could not find a buyer for the rest.

Francis March seems to have been a regular transatlantic traveller because in 1718 he again returned to England where in the meantime Anne Ellis had become administratrix of the Will of her sister-in-law Elizabeth Grace Ellis. The four Ellis children now being orphans their aunt Anne Ellis was named as their “next friend” and a group action was taken in the Court of Chancery to demand that Francis March should produce accounts of what had happened to the various Ellis properties. Many of March’s papers were still in Jamaica but he did produce a formal response and then returned to Jamaica in 1721.

By this time the two Ellis boys had reached the age of seventeen (the age at which they were to inherit) and their sister Mary had married John Manley who appears to have been somewhat older than the Ellis children and to have acted for them in their minority.

The Ellis family now took matters into their own hands and forcibly occupied all the property that had belonged to John Ellis senior, to his son Major John Ellis and to Carlton Goddard, including the land bought from George Cooke by Francis March with his own money! Moreover they also took possession of all the stock of slaves, cattle and equipment, and produce in the form of sugar and rum which March later valued at over £12,000 Jamaican currency and they took all the regular income from the plantations.

Having expelled Francis March they then exhibited a bill of complaint in the Jamaican Court of Chancery against him to which March duly responded. By this time the third John Ellis had died and the seized estates were being managed jointly by his younger brother George Ellis and John Manley.

Francis March was forced to sue for the money that he had laid out in paying for the land the second John Ellis had committed to purchasing from Carlton Goddard as well as paying off Goddard’s debt in order to secure the purchase. Moreover according to March the legacies due to Anne Ellis and to his two children as well as to the poor of the parish of St Catherine’s had still not been paid.

By this time Frances March had been in Jamaica on and off for many years and like so many colonists his health and that of his family was suffering. He sent his son ahead to England and prepared to leave the island with the rest of his family at which point the Ellis contingent threatened him with an injunction to prevent him leaving the island while what they claimed was a debt to them was still outstanding. This was a common procedure since it was not unusual for debtors to try to escape Jamaica leaving their debts behind them. Desperate to get back to England Francis March paid the Ellis family the amount that they had counterclaimed and left on a ship called the Resolution.

His troubles were far from over for the ship caught fire and March lost most of his possessions, including all his accounts and papers, and he and his family barely escaped with their lives. Back in London by 1724 John Manley was already dead as was Abigail Demetrius, George Ellis had reached the age of 21 and Francis March again attempted to enforce on George Ellis the payment of the legacies due under the Wills of his grandfather John Ellis and his father.

Westminster Hall where the Court of Chancery sat

(source: Wikipedia)

Once again Frances March petitioned the Court of Chancery, this time in London, in an attempt to get the whole confused mess finally resolved by asking the Court to require George Ellis to agree to pay him £3794 Sterling, the amount he had disbursed on behalf of the Ellis family. Given the size of the profits from their estates their is no reason to assume they could not easily have afforded this.

Sadly I am not aware of any record to indicate that George Ellis did finally pay up.

Francis March died in about 1736 and the Ellis family continued to prosper in Jamaica acquiring further lands, including the Montpellier estate from Francis Sadler Hals who received it as reward for his efforts in the Maroon War settlement of 1739. There is a very good account of the Ellis family’s various holdings and acquisitions in Barry Higman’s book Montpelier Jamaica: A Plantation Community in Slavery and Freedom 1739-1912.

I wrote on a previous occasion about the fate of George Ellis’s son John Ellis and his two great nieces Anne Maria and Bathshua Herring Ellis, who were all lost at sea in the great storm of 1782 when two of his servants had an absolutely miraculous escape.

Note: I have to thank David M Oakley without whose hard work transcribing a key legal document this posting would not have been possible.