By way of an occasional post, this is an illustration of why you should never give up on a brick wall.

Many years ago I discovered the wonderful Augier sisters, their name recorded sometimes as Hosier, and the name of the father who freed them in his Will was John Augier.

He was that mystery person, the one you can never get beyond, whose origins remain mysterious. But he is also an example of why it is always worth re-visiting those brick walls.

Recently I have been concentrating on local history in England. But this week I was contacted by an Augier descendant which sent me back to look at my previous research.

New material is added to online resources all the time and with help from a relatively recent family tree on Ancestry, and a new search for John Augier in other sources, I think I can update what I know about him through a story of piracy in 1671 and naturalisation in 1693.

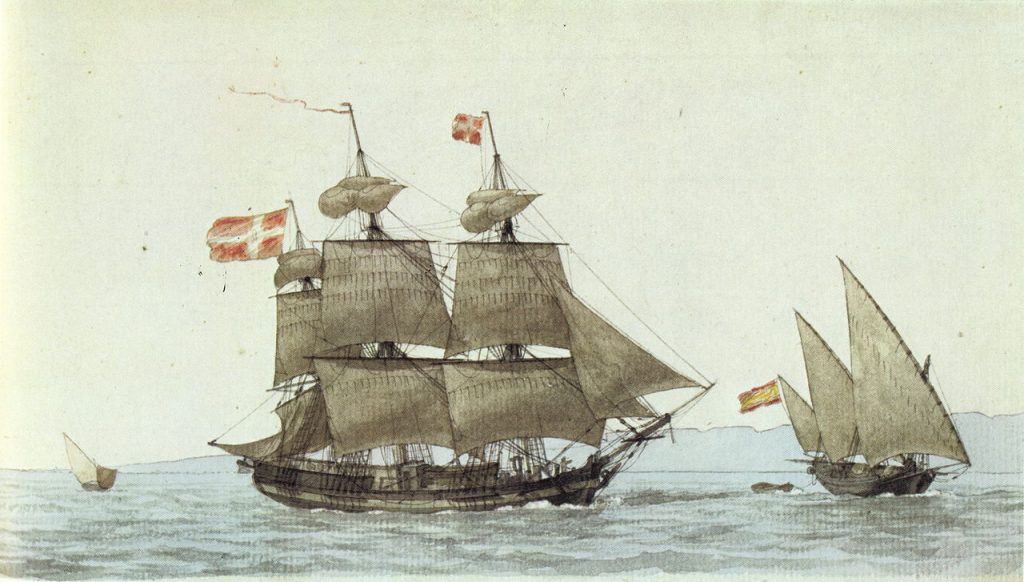

In May 1672 Peter Brent, Serjeant Plumber to his Majesty, and John Augier, part owners of the pink Peter of London presented a petition for compensation following the seizing of their ship whose other owner was Charles Cogan1. A ‘pink’ was a small ship with a narrow stern, derived from the Dutch word pincke meaning pinched. They had a large cargo capacity, were generally square rigged and the larger type were used in the Atlantic trade.

On board the ship, sailing from Jamaica to New York in August 1671 were the master Thomas Wayt (or Weight); John Patten a merchant, who lost in money, goods, and plate to the value of £300; Simon Reynolds and Nathaniel Radcliffe, gentlemen; merchants Richard Cook, John Pate, Robert Wendall, John White and Richard Elliot who claimed £1,435 between them. Thomas Wayte claimed £40 and Charles Cogan £1,000. All these made their claim in Jamaica in January 1672 and in May Peter Brent and John Augier claimed a further £1,000. The claims were recorded in the Calendar of State Papers, Colonial, America and West Indies which can be viewed in British History Online.

Those on board the ship, which was seized by a Captain Candelero of the St. Francisco, were taken with the ship to Campeachy (now Campeche) in Mexico. They were stripped of their clothes and possessions, had their trunks ransacked and their papers taken in spite of telling Candelero that a peace treaty was now in effect. The ship was stripped of sails and rigging before the crew and passengers were eventually released. Presumably Candelero had no use for the ship itself or not enough men to crew it.

Now here’s a small puzzle.

If John Augier part owned a ship trading between Jamaica and New York in 1671 he must have been at least in his early twenties. If he fathered daughters in the first two decades of the eighteenth century he was by then quite an old man for the times. So could the man who freed his enslaved children have been the son of the part owner of the Peter? I have found no baptism record to confirm this, but Kingston parish records do not exist before 1721.

On 05 September 1693 John Augier and his business partner Peter Caillard (who later had children with John’s daughter Susanna) both obtained naturalisation in Jamaica.2 Earlier, on 15 April 1687, a Peter Caillard was one of hundreds of Huguenot refugees naturalised by the Crown.3

My first reaction was that this must mean that John Augier was probably a French Huguenot, and correspondence in French to Caillard and Augier from the Huguenot Crommelin family, who were using them to forward correspondence to Daniel Crommelin, might support this.4 At the time of this correspondence Caillard and Augier were based in Kingston.

The John Augier who obtained naturalisation in 1693 may have intended to patent land in Jamaica which he could not do if he was not British. Perhaps having started out trading in enslaved Africans and goods exported from Jamaica to America and England, he also wanted to settle permanently in Jamaica and profit from ownership of a plantation.

Alternatively it is possible that rather than being French John Augier was the son of a British citizen, but had been born abroad and was thus regarded legally as an alien who would have to become naturalised in order to own land in Jamaica. This situation changed in 1700 after which the children of British citizens born abroad were regarded as British.

More detail might be added to the story of John Augier by examining Jamaican land patents with which the naturalisations were recorded. These have been microfilmed but are not online.

Because Augier is a relatively uncommon name I think it is reasonable to conclude that the man who was part owner of the ship Peter sailing from Jamaica in 1671 was either the father or the grandfather of Susanna Augier and her sisters. Also that he was in partnership in Kingston, trading in enslaved Africans and Jamaican produce, with Peter Caillard the father of some of his many grandchildren, and that he owned property in the parish of St Andrew where his daughters Jane and Sarah were baptised (albeit the transcriptions have different spellings of the surname).5

- ‘America and West Indies: May 1672’, in Calendar of State Papers Colonial, America and West Indies: Volume 7, 1669-1674, ed. W Noel Sainsbury (London, 1889), pp. 354-364. British History Online http://www.british-history.ac.uk/cal-state-papers/colonial/america-west-indies/vol7/pp 354-364 [accessed 1 September 2024]. ↩︎

- Bockstruck, LLoyd DeWitt. 2005. Denizations and Naturalizations in the British Colonies in America, 1607-1775. Baltimore, USA. Genealogical Publishing Company. p.9. https://www.ancestry.co.uk : accessed 05 September 2024. ↩︎

- Agnew, C.A.1871. Protestant Exiles from France in the Reign of Louis XIV. London: Reeves and Turner, p.45. ↩︎

- https://www.crommelin.org/history/Biographies/Frederic/Year1694-3.htm ↩︎

- Baptisms (PR) Jamaica, St Andrew. 04 April 1710. AUGINE, Jane. Jamaica, Church of England Parish Register transcripts (Image 36). https://familysearch.org : accessed 05 September 2024.

Baptisms (PR) Jamaica, St Andrew.13 November 1712. AUGIRE, Sarah. Jamaica, Church of England Parish Register transcripts (Image 37). https://familysearch.org : accessed 05 September 2024. ↩︎