Much work has been done recently demonstrating the presence of people of African origin in the UK for far longer than had previously been thought, notably Miranda Kaufman’s book Black Tudors.

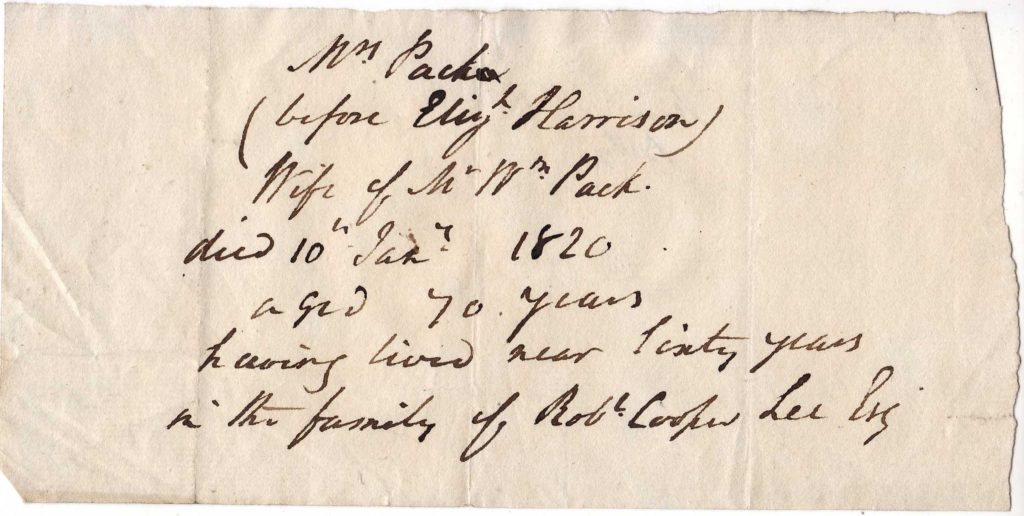

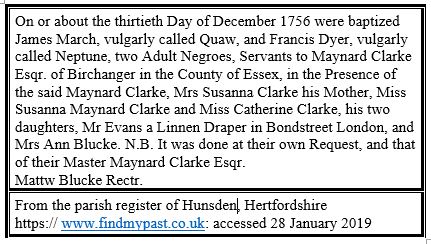

I recently came across the extract above in the parish register of Hunsden in Hertfordshire which highlights two more people whose origins would otherwise be unknown.

I have found no further record of who James March and Francis Dyer were, but their pre-baptism names suggest that James had retained his birth name and may have been a first generation slave, whereas Francis had been re-named by his owner. Possibly he may have been born in Jamaica to an already enslaved mother. Whether the names they chose at baptism were in any way connected with their parentage is not known.

However, we do know quite a lot about Maynard Clarke. He was the son of John Clarke and Susanna Maynard and was born in Jamaica in about November 1717. He was baptised in the parish of St Andrew on 25 November 1717, and his father died in about July 1720. Maynard was apprenticed in England to two attorneys and traded in partnership with various others with Jamaica. He married Jane Wood at Twineham in Sussex in 1739, and their daughter Susanna was baptised in London in 1743. Henrietta who died as an infant was baptised in Little Hadham, Hertfordshire in 1744. I have found no record of Catherine’s birth. A mis-transcription on FindMyPast has confused her with the record above.

Nearly twenty years after his father’s death Maynard took out a case in the Court of Chancery alleging that he had been defrauded of income from his estates. It seems likely that John Clarke had married Susanna, who owned property in Brixton in Devon and Sible Hedingham in Essex, hoping to improve his Jamaican affairs through his marriage settlement. He owned extensive properties and plantations in Jamaica, but must have been in debt, since shortly before his death, he had mortgaged some of it hoping to repay the debts out of the profits of his plantations.

Maynard Clarke’s first wife Jane Wood having died, he re-married in 1757 to Elizabeth Thompson and it seems that, despite a long time spent in England, he soon returned to Jamaica, for he died there about two years later aged about forty-one. Did James March and Francis Dyer return with him? Were they still enslaved or had they been freed?

The Legacies of British Slave-ownership website lists Maynard’s property in Jamaica when his Will was probated there in 1761. “Slave-ownership at probate: 211 of whom 113 were listed as male and 98 as female. 64 were listed as boys, girls or children. Total value of estate at probate: £12,680.77 Jamaican currency of which £8,855.75 currency was the value of enslaved people. ” I don’t have access to this document so don’t know if James and Francis were listed there.

After Maynard’s death, the Chancery Hall estate in St Andrew, once known as Clarke’s, became the property of Samuel Walter and later of his son of the same name. He left a life interest in it to his only daughter Mary Ann Walter, and thereafter it became the property of his great grandson Richard Lacy.

I have found no further record of Maynard’s daughter Catherine, but Susanna Maynard Clarke was buried on the 16 August 1772 in Hammersmith. She left all her property in England and Jamaica to her ‘only two friends’ – Mrs Ann Musgrave, a widow who ran the school in Hammersmith where Susanna died aged twenty-nine, and Miss Rebecca Thompson, Ann Musgrave’s niece.

Ann Musgrave made her Will the day before Susanna’s funeral, on 15 August 1772 leaving everything to Rebecca Thompson and died a year later. Rebecca lived till 1816, having remained unmarried, and left a substantial inheritance to her god-daughter Rebecca Flower.

All of which sadly demonstrates how much easier it is to find out about those who kept people enslaved than about the slaves themselves. However, if descendants of James March, alias Quaw, or Francis Pryor, formerly Neptune, are searching for them this may just help in that search.