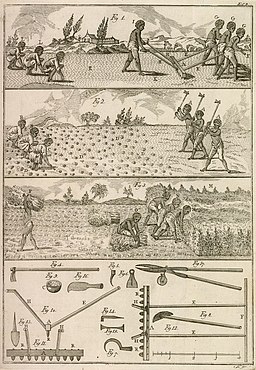

Cover image from Wet Nursing by Valerie Fildes*

Cover image from Wet Nursing by Valerie Fildes*

In January 1784 Frances Lee wrote from Bath to her brother Richard, “ The Duchess of Devonshire is here but she goes little into Public as she is at present a nurse – a very extraordinary circumstance in these refined times”.

At a time when it was unfashionable for the upper classes to breast feed their own infants, the Duchess of Devonshire’s insistence on doing so was much remarked upon. It was also disapproved of by the Duke’s family. The child was a daughter, there was great pressure on the Duchess to produce a son, and it was well known that breastfeeding would delay the chances of her getting pregnant again.

Before the easy availability of contraception a woman who was lucky enough to keep her health and survive childbirth, might expect to deliver eight or a dozen children and sometimes more. The Duchess of Lennox who was married at seventeen, and after the birth of her first child advised not to breastfeed because of a fear of making her “weak eyes” worse, produced twenty-two living children in thirty years[1].

When researching family history a useful rule of thumb is to expect one child every 18 to 24 months on average, and if you find a large gap in the record this generally indicates a lost pregnancy, or a missing record. Using this principle I successfully tracked down thirteen of the fifteen children of a family who spent the last four decades of the 19th century moving hither and thither across England building and repairing the railways. I knew there were fifteen children to find because half way through my researches the 1911 census became available. For the first time the 1911 census gives information on the number of children born to a couple, and whether alive or dead. Had I been prepared to spend more money guessing which birth certificate to purchase (the family name was a common one and often misspelled) I might have been able to find the last two children.

It seems clear that it was well known for centuries that breastfeeding limited the chance of getting pregnant and of course there was no real substitute for human milk. Babies might be fed on cows milk, often contaminated and a source of tuberculosis, or on pap – a mixture of flour and water. Weaning generally took place from a child’s second year, which helps to account for high levels of infant mortality as the child was exposed to a wider range of risks. Teething is often recorded as a cause of death both in parish records and later on death certificates and was regarded as particularly dangerous for the child. However it is more probable that infections picked up as a result of weaning with contaminated food were the cause, although the practice of lancing a child’s gums to encourage the teeth to come through would also have introduced infection.

The women who were employed as wet nurses came from a variety of backgrounds. Overtly the only qualification was to have a plentiful supply of milk to feed a baby, and in some cases particularly among poorer women this resulted in professional wet nurses who farmed out their own babies in order to obtain employment. In many cases they would have been women whose own child had just died. The fate of a child whose mother had died in childbed depended entirely on immediately finding a wet nurse.

For those employing them the moral character of the wet nurse was important, not only might a single mother be a threat to the marriage if she was a “loose woman”, but it was believed that more than nutrition flowed with mother’s milk, moral character might also. Some medical texts advocated that the wet nurse’s own child should be of the same sex as the one she suckled – some thought mothers of boys produced better quality milk and others that inappropriate sexual characteristics might be transmitted in the milk if the babies were of different sexes. There was also medical discussion as to whether a mother’s milk improved or deteriorated as her baby grow older and therefore whether the age of her baby relative to the age of the one she nursed was important.

For the wealthy upper classes there is evidence that the wet nurses they employed came not from the poor or single mothers, but from the social class immediately beneath them. One study of the wet nurses employed by Sir Roger and Lady Mary Townshend in the 17th century[2] shows that the women were the wives of prosperous yeoman farmers and other respectable local people who had previously been servants in the Townshend household and were consequently well known to the family.

When we come to the colonists in Jamaica and the wealthy families of the plantocracy we can see that they had a dual problem in finding wet nurses for their children. Although white society in Jamaica was more socially fluid than in England, it was relatively small in number and generally lacking in the intermediate social class of respectable white servants, yeoman farmers and well to do village craftsmen from whom Sir Roger Townshend’s family drew its wet nurses.

White women were always a scarce commodity in eighteenth century Jamaica. Moreover death and disease took their toll so rapidly on new white settlers that the numbers of white women were further reduced and the numbers among them who might potentially have been available as wet nurses were very small indeed. And yet although the pressure for women to breastfeed their own children must consequently have been greater the impression given by the spacing of baptisms suggests otherwise. There is enough evidence to be found in the spacing of plantocracy families, baptising one child a year over a period of the decade or so, to suggest that many of the women were not breast feeding their own children, although this conclusion is necessarily speculative as it is not always possible to establish whether the child lived to grow up. For example Elizabeth Langley the wife of Dr Fulke Rose, one of Jamaica’s early settlers, produced eleven children baptised between May 1679 and April 1694, and a further four children with her second husband Sir Hans Sloane.

The dilemma for white women in Jamaica who did not breastfeed their own children was whether to employ a black wet nurse. Just as medical opinion recommended that the wet nurse’s child should be of the same sex, and debated the nutritional quality of the wet nurse’s milk, so there was debate as to what adverse effects being suckled by a black woman might have on a white child. Both Sir Hans Sloane, and later the Jamaican historian Edward Long commented on the fact that planters avoided the use of black wet nurses.

“Planters eschewed black nurses ‘for fear of infecting their children with some of their ill-Customs’. The blood of black women was ‘corrupted’ and their milk ‘tainted’, differing distinctly from that of European mothers.”[3]

In the 1780s William Dwarris wrote proudly that his wife fed her babies herself “which I assure you is rather uncommon here”. His wife Sarah regarded breastfeeding as a means of birth control and recommended it to her sister. She also disapproved of the custom of using black and mulatto wet nurses. “I should be very unhappy to have him suck a Negro, there is I think something unnatural in seeing a white child at a black breast besides that of being obliged to put up with their ill manners for fear of hurting your child.”[4]

There was an additional practical problem, that of the low birthrate among female slaves. Much literature has been produced both about white society in Jamaica failing to reproduce itself and increase in numbers in the way that it did in North America, and about the problem that planters faced owning a slave population that did not reproduce itself let alone increase. Only after the cessation of the slave trade did planters in general make effective efforts to encourage the natural reproduction of their enslaved workers. So enslaved black women who might have welcomed the relatively easier work of wet nursing, were deprived of the opportunity by their own low fertility rates, by the relatively small numbers of pregnant plantocracy wives and by the prejudiced fears of contamination among the whites.

It may be that white families in Jamaica sought wet nurses among the mixed race women of their servant class, whose social status was more akin to that of the wet nurses used in England and whose ‘diluted’ colour might be thought to diminish any supposed disadvantage. I’m not aware that any study has been done on this however.

There are few documented references to family wet nurses other than in the kind of estate accounts used for the study of Sir Roger Townshend’s family. I have however come across the following in the Will of Major General Samuel Townsend (no relation) whose wife Elizabeth Aikenhead (born in Jamaica about 1734) was the widow of Gilbert Ford (Attorney-General for Jamaica 1760, Member of the Assembly for St. John’s 1761, Member of Council 1764, died 1767):

“I give devise and bequeath unto my present Housekeeper Mrs Mary Collins the Sum of Ten Pounds Yearly for and during the term of her natural life as a mark of my intire approbation of her fidelity and good behaviour as well as of her great care and unvaried attention to my children whom she suckled.”

Mary Collins was clearly a much loved member of the household, for when Elizabeth Townsend died in 1800 she left her £150. Incidentally we also know that Mary was literate since in 1796 she signed an affidavit concerning the validity of the handwriting in the Will of Elizabeth’s sister Milbrough McLean.

[1] Stella Tillyard, Aristocrats:Caroline, Emily,Louisa and Sarah Lennox 1740-1832, Chatto and Windus ,1994

[2] Linda Campbell, Wet-Nurses in Early Modern England: Some Evidence from the Townsend Archive, Medical History, 1989, 33:pp.360-370.

[3] Barbara Bush, Slave women in Caribbean Society 1650-1838, Heinemann Publishers (Caribbean) Kingston, Indiana University Press, James Currey, London 1990, p.15

[4] Lucille Mathurin Mair, A Historical Study of Women in Jamaica 1655-1844, University of West Indies Press, 2006, p. 119.