Egmont Villa, Fulham, the last home of Theodore Hook (from The Man who was John Bull)

I dislike loose ends. Last week I ended the piece on Berners Street with a brief reference to Theodore Hook and the hope that his family had not starved after his early death on the 24th of August 1841 at the age of fifty-two. So I have spent the last week finding out what happened to them all.

Various 19th-century works recalled the life of Hook and there is a comprehensive modern biography written by Bill Newton Dunn*, who happens to be the Member of the European Parliament for the area where I live. When he was writing it, in the late twentieth century, there were not the online genealogical resources that are now available to us, and so I have had the advantage of being able to find out a little more of what happened to the Hook family than he could.

Theodore Edward Hook had lived for many years with Mary Anne Doughty, and they had at least six children together. In 1828 he wrote a Will in which he referred to them having ‘six children still living’ and requesting his executor and trustee to make provision for his children and their mother. That his brother and one of his nephews had distinguished careers in the Church of England may partly account for the total omission of Mary Anne and and her children from a later 19th-century Hook family tree, and I had feared that the family had been left in total poverty and had perhaps ended up in the workhouse.

In many ways Hook was an 18th-century character. Incredibly talented at improvising both music and verse, endlessly cheerful and good-natured and a bon viveur who increasingly drank more than was good for him, he was an energetic prankster and hoaxer but also an extremely hard-working writer and satirist.

He himself noticed the change in moral tone as the nineteenth century progressed, writing in one of his stories It sounds odd, and even absurd to say so, but true it is, that religion has become fashionable, and its cultivation and pursuits have taken place of what in the days of our grandfathers were called spirit and humour, which in plain English, meant profligacy and dissipation. No midnight broils now break the public peace, no feats of drinking are recorded in our periodical papers as matters of admiration. It is no longer thought brave to beat the watch, nor considered extremely wise to break the lamps; quiet lodgers are now never aroused from their slumbers by bell-ringings of the “Tonsonian school,” nor are waiters thrown out of tavern windows, and charged in the bill.**

That Theodore and Mary Anne lived together without marrying is another example of his 18th century character and whether he eventually married Mary Anne Doughty seems to be in question. It is suggested that they married in 1840, but I have not been able to find any record of such a marriage although it is always possible that they married in France whence Theodore’s father James Hook, noted for having composed the song Sweet Lass of Richmond Hill, had fled on hearing of Theodore’s £12,000 debt incurred in Mauritius. Although it was judged that Theodore had no criminal case to answer, the civil debt hung over him all his life and at his death all his goods were seized.

Although six children are mentioned in the 1828 Will, a contemporary wrote that only five were still alive at the time of Theodore’s death – two sons and three daughters. Only three were living in the family home, Egmont Villa Fulham, when the 1841 census was taken, these were Mary, Louisa, and William. The elder son Frederick Augustus had already left for a military career in India. Who the fifth surviving child was remains a mystery since it has proved impossible to find baptism records for any of the Hook children, and most of Theodore’s many diaries have disappeared. I had wondered whether the free spirited Theodore did not believe in baptism, but in his writing he comments favourably on attending the christenings of friends’ children. The impediment may have been the children’s illegitimacy or it may simply be that the records are not available online either under the name of Hook or Doughty. It is also difficult to establish with certainty when the children we do know of were born, although Mary was probably born about 1821 in the parish of St Pancras; Bill Newton Dunn gives Frederick’s birth as the 24th of June 1823, and Louisa seems to have been born about 1824 in Kentish Town, with William being born in Fulham in 1828. It is likely that the two missing children fell between Louisa and William.

Immediately after Theodore’s death various friends contributed subscriptions for the support of his family, so the rapid descent into the workhouse that I had feared was avoided. However the total amounts were not huge and many who might have contributed appear to have declined to offer support to illegitimate children!

The next we hear of any of them is the marriage of Louisa to Frederick Annesley on the 13th of October 1842 at St Paul’s Canonbury in Islington. On the marriage record Louisa is said to be of full age, which she may not in fact have been. Frederick’s occupation is given as solicitor like his father, and the couple both gave the same address at 9 Maberley Terrace. They went on to have at least four children before Frederick’s early death in about 1868, and there were Annersley descendants well into the twentieth century.

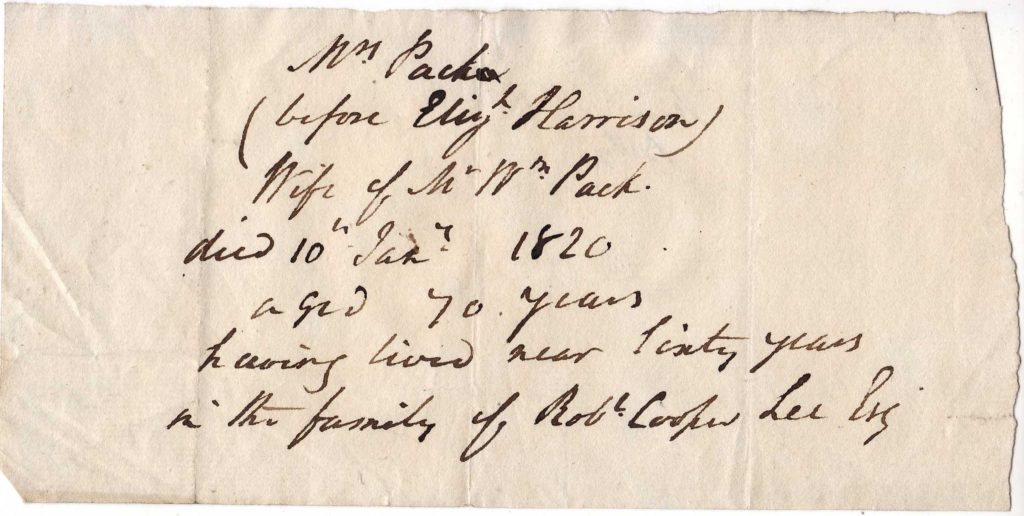

One of the witnesses at Louisa’s wedding was her sister, who signed herself Mary Catherine Hook, and the next clue to her whereabouts comes in a letter to The Morning Post in December 1892 by Algernon Ashton who had been concerned at the dilapidated state of Theodore Hook’s tombstone and following publicity over this had been contacted by Mary, who was then living in reduced circumstances in Agnes Terrace, Leytonstone. Ashton gave her name as Mrs Mary St C Tanner, and as a result I was able to find her in 1851 living as a widow with her mother and brother William at 7 Clarence Place, High Street, Camberwell. I cannot find any record of a marriage of Mary Hook with someone called Tanner and so wonder whether she was in fact twice widowed between 1841 and 1851, and had married Mr Tanner under a different name. Whether the reason for them living in Camberwell was that this was where Mr Tanner lived is unclear but in the 1851 census Mary is recorded as the widowed head of the household. She and her mother (who was recorded as Mary Hook, as she was also in the 1841 census) are both shown as annuitants and brother William is working as a clerk in the Post Office. They were sufficiently well off then to be able to afford a servant.

I have drawn a complete blank with the 1861 census, and wondered if perhaps the family was in France visiting James Hook’s widow Harriett, however a transcription error is perhaps the more likely reason. Mary Anne Doughty seems to have died before 1871 when we find William Hook and his wife Fanny living in Great Warley, Essex, where William is a clerk in a GPO Money Order Office. They have two children William and Alice Fanny, and Mary Tanner is living with them, still in receipt of her annuity. William probably died in the latter part of 1875 and the family moved closer to London where they remained in the Leytonstone area well into the twentieth century.

There is a further mystery attached to this unconventional family. In the 1891 census the widowed Fanny Hook was living with her son William, daughter Alice and sister-in-law Mary and a nephew called Frederick Hook who also appears in the 1901 census. Fanny died in 1894, aged fifty-nine and Mary St C Tanner died in 1902 at the age of eighty-one.

In 1911 William Hook completed the census return recording Frederick as his brother. Alice’s age was adjusted down by five years to forty-four while Frederick’s was adjusted up to twenty-nine. It seems highly likely that Frederick Samuel Hook, born in 1885, was the illegitimate son of Alice Fanny Hook and that William wished to conceal the fact.

And a final footnote, lest you think I have strayed too far from Jamaica.

Theodore Edward Hook had an older brother James, for whom incidentally he published two novels anonymously lest James’s reputation in the church should be damaged. In 1797 James married Ann Farquhar at St James, Westminster. Ann was the daughter of Sir Walter Farquhar, physician to the Prince Regent. Her mother Anne Stevenson had first been married to Dr Thomas Harvie of Jamaica.

I shall be taking a break from research over the Christmas period, but hope to be back with more eighteenth century tales in the New Year.

In the meantime may I wish you all a very Happy Christmas and a peaceful New Year.

It’s not too late to take advantage of the special December Discount on A Parcel of Ribbons!

*Bill Newton Dunn, The Man who was John Bull, Allendale Publishing, London, 1996 ISBN 0-9528277-0-0

**Newton Dunn, op.cit, p.300.